Hi Everyone and welcome back to the newsletter.

Today, we’re going to take a pause from music, and talk instead about sound. Namely, the gunpowder-based cacophony that defines the 4th of July across the United States.

For a lot of American readers, the 4th can feel like a complicated holiday, likely more so than ever these days. Hard to embrace a celebration defined by flag waving and BBQ in open-hearted support for a nation that’s careening towards…somewhere that feels darker every day. At best, it’s a great hang. At worst, it’s a restatement of a civic religion based around a set of beliefs that are, to put it mildly, honored in the breach. To a lot of folks, Frederick Douglass’s famous response is the correct one.

None of that is wrong. But it can also, I think, collapse a multi-layered history into a single perspective, as if American life was ever a simple projection of one-sided hegemony. It makes culture a conspiracy, rather than a struggle or a conversation. And in doing so, I think it devalues so many—too many—lived experiences. It erases millions of people who had the ability to make and find meaning in the world around them, meaning that shaped history and remains with us to the present.

Annnnnndddd I think you can get a sense of all of this, by talking about fireworks.

(Sam’s Field Recording—Brooklyn Soundscape, Random Night, June 2020)

Because, on the face of it, what we do with fireworks in this country is kinda weird. It’s obviously different state-by-state, but in NY, where Sam grew up and Saxon lives, they are both relatively illegal and socially acceptable—especially on the 4th, when blowing up stuff for no good reason is sort of de rigueur. But why? Why do we both ban and celebrate explosives, and what do they have to do with independence day?

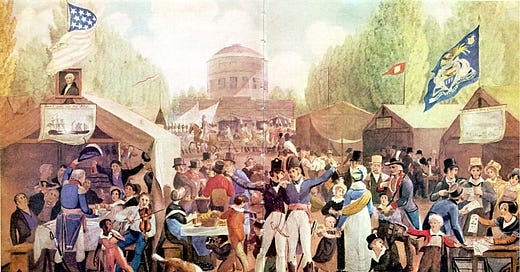

(An early, militarized, 4th of July celebration)

Turns out, it goes back a long way. Early in the nation’s memorial history, especially when veterans of the revolutionary war were still alive, the 4th of July was celebrated via civic rituals—pageants, parades, and military displays, with fireworks fitting right in. The early American republic was CRAZY about this kind of thing—they were figuring out how to legitimate a new political system without the benefit of king-style time immemorial, and a wide array of carefully organized events were vital for symbolically constituting the body politic.

Things got more complicated, of course, as time went on, and more than one group sought to claim the power of this revolutionary nationalism for their political/social demands. Think journeymen workers and small-scale artisans, being squeezed by the beginnings of industrialization and eager to display their social importance, coming up against reformist businessmen, who were hoping for a more orderly and restrained celebration in a moment of rising class tensions. (This particular conflict, however, gets more complicated when you remember that, at least in the North, the businessmen were more likely to be abolitionists, and the workers increasingly invested in the language of White privilege.)

(Fighting over the 4th in 1830s New York)

These tensions—with workers’ picnics + bosses summer retreats coming into social, if not spatial conflict—only deepened as the 19th century drew to its close and wave after wave of new immigrant groups entered the country. Many of these groups, from Protestant Germans to Catholic Italians and Czechs, enjoyed drinking quite a bit more than the now teetotaling middle classes of “native born” Americans. With the 4th of July an established tradition, and frequently one of the few holidays that workers received, celebrations began to take on a new layer of meaning. It was, after all, harder to decry the degenerate excesses of the lower classes if they were, you know, earnestly celebrating the nation’s birth. By the same token, loudly placing themselves within the central traditions of American life allowed these groups to claim a space within the country and its history. Using the opportunity to take over the public spaces of the city with fireworks, tie patriotic nationalism to multi-ethnic partying, and get under the skin of the elites all at the same time? Hard to say no.

So, by the turn of the 20th century, the aural battle-lines were fairly well drawn. On one side, a rawkus tradition of democratically organized controlled demolition. On the other, a set of progressive style reformers castigating the day for its noise, disruptions, disorderliness, and danger, and preaching the need for a “safe and sane” holiday. And really—we’ve more or less stayed there ever since, with new experiences—WW II, suburbanization, the automobile, micro-targeted post-60s consumerism, you name it—just adding layer after layer of meaning on top of an already-conflicted 19th century foundation.

Walking into your local supermarket, and facing a giant array somehow constructed out of Bud Lite, it can be hard to feel the presence of those Jacksonian artisans or turn-of-the-century Czechs, but…they’re there, their histories still shaping the contradictory dynamics of our patriotic carnaval. So how to feel about the fourth of July? It’s tricky. But t ignoring all of those alternate and counter traditions is maybe as big an issue as waving a flag without worrying about what it’s been doing.

Department of Real Music:

Saxon: When I think of the good parts of America, I think of John Coltrane. This is one of the classics.

(Sam: And few things are more obviously American than an African American musician undertaking a revolutionary rethinking of a composition by two Jewish Broadway songwriters, who got their start in an industry based on remaking the products of Black Ragtime, which were in turn initially marketed within the long-standing structures of Blackface Minstrelsy.)

Sam: Mississippi Fife and Drum music is one of America’s great musical traditions—funky, wild, somehow bridging the gap between the revolutionary war and the Chevy.

Saxon and Sam